Mohsin Mudassar

Material Conditions:

At the turn of the twentieth century, Imperial Russia had minimal industrialization. The hub of the Empire, European Russia, and a part of Ukraine had a population of 92 million in 1897, with the total population of the Empire recorded by that year’s census at 126 million. Out of this population, 80% were peasants who used old farming methods and practices and, as such, had low yields and productivity. There were only 3 million permanent industrial workers. Furthermore, there were only a few large cities. Seasonal laborer peasants went to cities and mines to work but would come back to their villages. Russia’s peasants had a history of dissent with frequent uprisings. The working class, with strong ties to the peasantry, was also fairly revolutionary with Russian workers having frequent general strikes. During this time, the Imperial government was trying to industrialize the country, and the Empire was going through a process of modernization

Socialist Movement in Russia:

There were several trends in the Russian Socialist movement. The Russian intelligentsia was a Westernized elite that believed in the betterment of Russians through modernization. They considered themselves a classless group of altruistic individuals united by a radical ideology. Most of them were utopian socialists. Many Russian Marxists were also a part of the intelligentsia and believed that Russia must pass through capitalism first; there needed to be first a bourgeoise revolution and then a socialist one according to them. The Russian Social Democratic Labor Party concerned itself mainly with educating the workers with Marxist ideas through study circles. The other major trend in Russian Socialism was populism. Populists opposed capitalism and idealized the peasantry and rural life. They were opposed to industrialization due to its destructive impact on the masses, and the social fabric. The main problem faced by the Russian Socialists was of getting ready for the revolution after the next.

Bolshevik-Menshevik Split:

In 1903, the RSDP held its second congress where a dispute arose between Lenin and Plekhanov over the editorial board of the party newspaper.The Bolsheviks were led by Lenin and the Mensheviks by Plekhanov, Martov, and Trotsky. The Mensheviks were a more diverse and larger group. Initially, it was thought that the two would reconcile but over time they developed into increasingly distinct groups. Lenin believed smaller groups are more successful and his faction came to be perceived as more radical. Some people also attributed his liking of smaller groups to his difficulty in tolerating disagreement—that ‘malicious suspiciousness’ that Trotsky called “a caricature of Jacobin intolerance” in a prerevolutionary tirade.

After the split, Bolsheviks became known for being radical, militant, and close-knit. They had a single leader and were characterized by their ideological unity, strict discipline, centralization, and belief in achieving a revolution. They were made up of professional revolutionaries who were willing to do whatever it took to achieve their goals. In contrast, the Mensheviks were seen as more moderate and non-militant. They were perceived as being closer to the bourgeoisie and were not as willing to engage in extreme tactics to achieve their goals.

Lenin, at the time, viewed Russia as “the weak link in the chain of imperialism.” He believed that this made it the best and easiest place to disrupt the global capitalist order. Lenin saw the laboring masses of the semi-periphery as the foundation of the anti-capitalist “proletarian resistance,” and believed that they could build an alliance with “democratic, national independence movements” fighting colonization. He saw this as a way to advance the cause of socialism and achieve a global revolution.

Government Failures

Imperial Russia during WW1 was characterized by a lack of efficient administration, with soldiers often fighting without adequate supplies such as ammunition or boots. There was also a significant lack of military training, compounded by the fact that Jews were being subjected to pogroms. This undermined trust in the state and made it difficult for the government to rally support for the war effort. In response, Zemstvos were established, which functioned as parallel institutions doing the work that the state was supposed to do which further highlighted the failures of the state to provide for its citizens. At the head of it all was Nicholas II, who was seen as incompetent and unconcerned about the welfare of his people. These factors contributed to a widespread sense of disillusionment and ultimately played a role in the downfall of the Russian monarchy.

February Revolution:

The February Revolution of 1917 began on March 8th, with women-led protests that quickly evolved into a broad movement against Russia’s involvement in World War I. The protests forced the Tsar to resign, and the Duma, Russia’s parliamentary body, formed a provisional government with members from all ideological backgrounds. Meanwhile, workers revived the Soviets, or councils, that they had used during the 1905 Revolution. The Soviets became powerful political bodies that represented the interests of the working class and challenged the authority of the provisional government. Overall, the February Revolution marked a significant turning point in Russian history, ushering in a period of political and social upheaval that ultimately led to the fall of the Tsarist regime and the establishment of the world’s first Communist government.

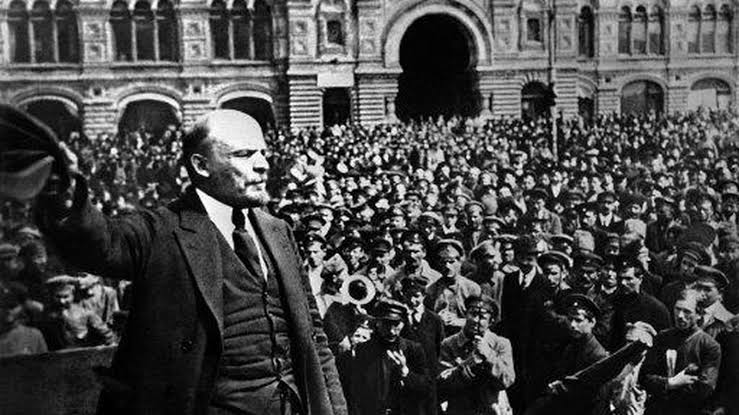

Lenin’s Return:

In April 1917, Lenin returned to Russia from Switzerland with the help of the German government. His return marked a shift in strategy towards party vanguardism, or the idea that a small, dedicated group of revolutionaries could lead the masses to revolution. By October of that year, around 20 million people had become members of the soviets, or councils, which represented workers and peasants in Russia. The Bolsheviks, under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, ran on the slogan of “Peace, Bread, Land,” promising to end the war, redistribute land to peasants, and provide food to the hungry. They organized from the grassroots, building support among the working class and using their influence within the soviets to push for their revolutionary agenda. Their strategies were dynamic and constantly changing, as they navigated the complex political landscape of the time. Ultimately, their efforts were successful, culminating in the Bolsheviks seizing power in the October Revolution and establishing the world’s first Communist government.

The October Revolution

The Revolution Itself:

The February Revolution in Russia was viewed by Lenin as a bourgeoisie revolution and raised the slogan of “All power to the soviets!” Alexander Kerensky, a social democrat, became the head of the provisional government in the summer, but his rule was met with significant opposition, including the July Days, during which Bolsheviks and other radical elements unsuccessfully attempted to overthrow the government. However, by August, the Bolsheviks gained a majority in both the Petrograd and Moscow Soviets, paving the way for their revolutionary agenda. Lenin saw the Fall as the opportune time for a revolution, but there was a sharp internal struggle within the party over whether to revolt or not. Eventually, the coup began at a meeting of the Soviets, with the Bolsheviks taking over arms depots, transportation networks, and other critical infrastructure. These actions paved the way for the October Revolution and the establishment of the Soviet Union.

After October:

In the wake of the October Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks quickly consolidated power in Russia. They began by holding elections for the constituent assembly in January of 1918, which the Socialist Revolutionary Party won. However, the Bolsheviks did not recognize the legitimacy of the assembly and forced its dismissal. This move demonstrated the Bolsheviks’ belief in the supremacy of the revolutionary guard and their unwillingness to accept any power above it.

After taking control, the Bolsheviks immediately nationalized industries, banks, and other key institutions, and started negotiating for peace with Germany and Austria-Hungary. They also took over the Zemstvos, local government bodies that had been set up in the late 19th century to improve rural governance. Power was increasingly concentrated in the hands of the Soviets, and the Bolsheviks worked to create a more centralized and efficient state apparatus.

Despite Lenin’s hopes for a wider European socialist revolution, such dreams did not materialize, and the Bolsheviks found themselves isolated on the international stage. They were forced to accept the harsh terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which ended Russia’s involvement in World War I but required significant territorial concessions to Germany. Lenin reluctantly agreed to the treaty, but it was a bitter pill for the Bolsheviks to swallow, as they had hoped for a different outcome.

Civil War:

After the Bolsheviks took power in October 1917, they faced immediate threats to their fledgling regime. One of the most significant threats came in the form of an officer’s counter-revolution, which saw some generals of the Imperial Army attempt to overthrow the new government. This counter-revolution was supported by France, the UK, and the US, who saw the Bolsheviks as a threat to their own interests.

In the spring of 1918, these foreign powers began to intervene more directly in the Russian Civil War. British, French, American, German, Canadian, and Japanese troops invaded Russia, each with their own strategic interests in mind. The British were based in Murmansk, the French, US, and Canadian troops were in Archangelsk, the Japanese were in Vladivostok, and the British and Turks were in Baku and the Caucasus.

Despite the challenges posed by these foreign interventions, the Bolsheviks were able to maintain their hold on power. They did so in part by recruiting former officers of the Tsar’s army into the Red Army. In fact, 44 percent of the Red Army’s command structure was made up of former officers, many of whom were able to bring valuable military expertise to the new regime.

Aftermath

Putsch or Revolution:

The Russian Revolution is a subject of much historical debate, with some historians, such as Weber, referring to it as a putsch. This comes from the idea that somehow; the Russian Revolution replaced the aristocracy and bourgeoisie with the party and state bureaucracy. This is an anti-historical narrative as the revolution resulted in a complete overhaul of the economic and political system of the Russian Empire. The policies of War Communism in addition to the social and political policies of the Bolsheviks were a complete departure from the days of the Imperial government. The revolution led to mass radicalization and the organization of the Red Army, which played a crucial role in defending the new socialist state against internal and external threats as well as winning the Civil War.

The NEP and Other Policy Concessions:

The New Economic Policy (NEP) was a significant policy concession that was introduced by Lenin’s government in 1921 after the end of the Civil War to replace War Communism. The policy aimed to revitalize the Soviet economy, which was suffering from the aftermath of World War I and the Civil War. The NEP was a blend of capitalism and socialism, where the government retained control over large industries, banks, and foreign trade while allowing private ownership of small businesses. Under the NEP, peasants were allowed to sell their surplus crops in the market, and private businesses were permitted to operate. The NEP was intended to promote the growth of industry, and it proved to be highly successful in stimulating economic recovery.

Political and Social Policies:

The Soviet Union’s political policies were also totally different from the preceding Tsarist and republican regimes. One of the first acts of the revolutionary government was to grant suffrage to women along with the right to abortion. These would have been inconceivable under any other government since Russian society at large was socially conservative and patriarchal. These actions showed the commitment of the Communists to the liberation of women.

The Union of Soviet Socialists Republics (USSR) was established as a one-party state with a complex system of representation through “councils” or soviets. The soviets were divided into two tiers; the first tier consisted of local soviets, which were directly elected by workers, peasants, and soldiers in each town, village, or factory. The second tier was composed of regional and national soviets, which were elected by the lower-level soviets. The soviets had the power to pass laws, elect government officials, and make decisions on economic and social policies.

However, Soviet democracy often suffered due to the constant interference from the imperial and capitalist powers which resorted to destabilizing the newly established state after their attempt at direct invasion failed. Due to this, the state had to develop safeguards for rooting counter-revolutionary elements working on behalf of the imperial powers. This sometimes resulted in inadequate consideration for individuals’ rights to safeguard the interests of the working class at large.

Foreign Policy:

Initially, the Soviet leadership had hoped that the revolution in Russia would be followed by revolutions all over Europe as the war-weary toiling classes rose up to overthrow their masters. In this vein of revolutionary internationalism, the USSR extended its support to all national liberation movements across the globe. This remained a key part of Soviet foreign policy until its fall.

However, as the hopes of international revolution failed to materialize, the Soviet Union shifted towards a more moderate foreign policy which was accompanied by the rollout of the NEP at home. They sought to attract foreign investment to rebuild their economy and to industrialize. Additionally, the USSR pursued a policy of Mutual Respectability and good relations was intended to improve relations with the capitalist West, which had been hostile to the Soviet Union since its inception.

Legacy

The Russian Revolution stands, to this day, as the most prominent socialist revolution in the whole world. It was the start of an ambitious socialist project that embodied what a socialist horizon would look like. In the twentieth century, the USSR was a beacon of hope for all revolutionaries, progressives, and activists working for the eradication of all kinds of oppression and continues to be an inspiration for Marxists around the world. Its support for national liberation movements and socialist struggles all over the globe embodied what revolutionary internationalism could look like.

For socialists today, it is immensely important to be aware of the lessons of the Russian Revolution. As the single most important event of the twentieth century, the experiences of the revolution are relevant to this day, especially for those of us organizing in the Global South. Extracting these lessons and applying them to our contexts gives us insights into what we should and should not do. Moreover, in a time when capitalist realism has infiltrated even leftist spaces, it is important to remember that the socialist horizon embodied by the October Revolution is still achievable.

very awesome stuff bro